In the last few years word embeddings have proved to be very effective in various natural language processing tasks like classification. Kim’s Paper. The focus of the post is to understand word embeddings through code. This leaves scope for easy experimentation by the reader for the specific problems they are dealing with.

There are various fantastic posts on word embeddings and the details behind them. Here is a short list of posts.

- Natural Language Processing (almost) from Scratch

- Sebastian Ruder’s posts on word embeddings

- The actual Word2Vec paper and Xin Rong and Yoav Goldberg explained various parameters and details of the paper here and here

In this post, we will implement a very simple version of the fastText paper on word embeddings. We will build up to this paper using the concepts it uses and eventually the fast text paper. Word Embeddings are a way to represent words as dense vectors instead of just indices or as bag of words. The reasons for doing so are as follows:

When you represent words as indices, the fact that words by themselves have meanings associated with them is not adequately represented.

the:1, hello:2, cat:3, dog:4, television:5 ..

Here even though cat and dog are both animals the corresponding indices they are represented by do not have any relationships between them. What would be ideal is if there was some way each of these words had some representation, such that the corresponding vectors or indices were also related.

Bag of words also suffer from similar problems and more details about those problems can be found in the resources mentioned above.

Now that the motivation is clear, the goal of word embeddings or word vectors is to have a representation for each word that also inherently carries some meanings.

In the above diagram the words are related to each other in the vector space, thus vector addition gives some interesting properties like the following:

king - man + woman = queen

Now the details of how words embeddings are constructed is where things get really interesting. The key idea behind word2vec is the distributional hypothesis, which essentially refers to the fact the words are characterized by the words they hang out with. This essentially refers to the fact that the word “rose” is more likely to be seen around the word “red” and the word “sky” is more likely to be seen around the word “blue”. This part will become clearer through code.

Let’s start by using the Airbnb dataset. It can be found here. Also, I did some preprocessing but should be fairly easy to just extract the text field by loading into pandas data frame and getting the review column.

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv('AirbnbData/reviews.csv')

The data is quite interesting and there is a lot of scopes to use it for other purposes but we are only interested in the text column so let’s concentrate on that. Here is a random example of a review.

data['text'][4]

'I enjoy playing and watching sports and listening to music...all types and all sorts!'

Skip-Gram approach

The first concept we will go through is skip-gram. Here we want to learn words based on how they occur in the sentence, specifically the words they hang out with. (The distributional hypothesis part that we discussed above.) The fifth sentence in the dataset is “I enjoy playing and watching sports and listening to music…all types and all sorts!”. In order to create a training dataset for exploiting the distributional hypothesis, we will create the training batch which will create the word and context pairs for each of the words. What we want is, for each of the word, the words adjacent to that word to have a higher probability of occurring together and the words away from it, to have a lower probability. (Not quite true, essentially, words that are likely to occur together should have a higher probability than the words that don’t.) Eg: In the sentence “Color of the rose is red”, here we want to maximize p(red|is) and minimize may be p(green|orange) which is a noisy example.

The goal is to have a dataset, where we can distinguish if a word is present in a context and then mark it positive, else mark the word as negative. Keras has some useful libraries that lets you do that very easily.

import numpy as np

from keras.models import Sequential

from keras.layers.embeddings import Embedding

from keras.layers import Flatten, Activation, Merge, Reshape

from keras.preprocessing.text import Tokenizer, base_filter, text_to_word_sequence

from keras.preprocessing.sequence import skipgrams, make_sampling_table

Using TensorFlow backend.

The libraries we need have been imported above.

Just as a quick note, we will randomly sample words from the dataset and create our training data. There is a problem with this, though. The more common words will get sampled more frequently than the uncommon ones. For instance the word “the” will be sampled really frequently because they occur often. Since we do not want to sample them that frequently, we will use a sampling table. A sampling table essentially is the probability of sampling the word i-th most common word in a dataset (more common words should be sampled less frequently, for balance) [From, keras documentation].

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv('AirbnbData/reviews.csv')

vocab_size = 4000

tokenizer = Tokenizer(nb_words=vocab_size,

filters=base_filter())

tokenizer.fit_on_texts(data['text'])

vocab_size = len(tokenizer.word_index) + 1

word_index = tokenizer.word_index

reverse_word_index = {v: k for k, v in word_index.items()}

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from keras.layers import Convolution1D, MaxPooling1D

from keras.utils.visualize_util import model_to_dot

from IPython.display import Image

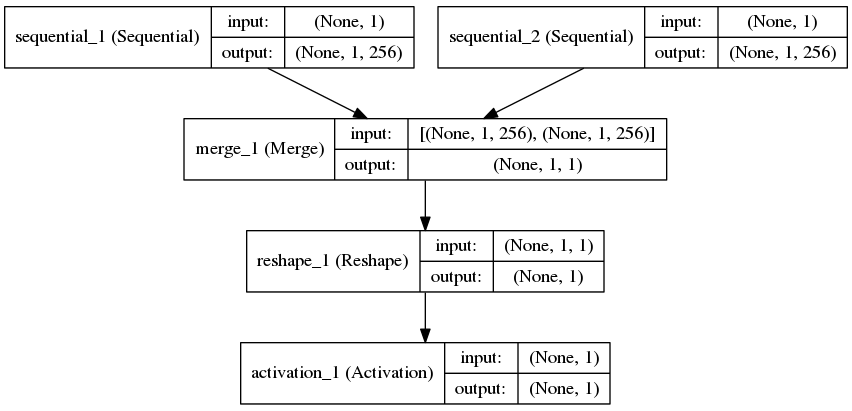

To go through the details of the model, we create target and context pairs first. More details on how to create these later. Then for each of the words, we represent the word in a new vector space of dimension 100. The layers “target” and “context” represents the two words and if the target word and the context word appear together in a context then the label is 1 otherwise a zero. This is how this has been framed together as a binary classification problem. So in our example,

‘I enjoy playing and watching sports and listening to music…all types and all sorts!’

The [target, context] pairs will be for instance,

[enjoy, I], [enjoy,playing] with labels 1 (since these words occur next to each other) and some noisy examples from the vocabulary [enjoy, green] with labels 0

embedding_dim=100

target = Sequential()

target.add(Embedding(vocab_size, embedding_dim, input_length=1))

context = Sequential()

context.add(Embedding(vocab_size, embedding_dim, input_length=1))

# merge the pivot and context models

model = Sequential()

model.add(Merge([target_word, context_word], mode='dot'))

model.add(Reshape((1,), input_shape=(1,1)))

# model.add(Flatten())

model.add(Activation('sigmoid'))

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='binary_crossentropy')

Image(model_to_dot(model, show_shapes=True).create(prog='dot', format='png'))

Just to go through the details of every step, when we did the dot product along the second axis in the Merge layer, we are essentially trying to find the similarity between the two vectors, the context word, and the target word. The reason for doing it this way is because now you can think of contexts in different ways. A context may not be just the words it occurs with, but the characters it contains. The char n-grams can be context. Yes, this is where the fasttext word embeddings come in. More on that later in this post.

But let’s dive into contexts a bit more and how specific problems can specify contexts differently. Now may be in your task you can define contexts with not just words and characters, but with the shape of the word for instance. Do similarly shaped words tend to have similar meaning? May be “dog” and “cat” both have the shape “char-char-char”. Or are they always nouns? pronouns? verbs? But you get the idea.

This is how we get the word vectors in skip-gram.

We will come back to skipgram again when we discuss the fasttext embeddings. But there is another word embedding approach and that is known as CBOW or continuous bag of words.

Now in CBOW the opposite happens, from a given word we try to predict the context words.

Subword Information

The skipgram approach is effective and useful because it emphasizes on the specific word and the words it generally occurs with. This intuitively makes sense, we expect to see words like “Octoberfest, beer, Germany” to occur together and words like “France, Germany England” to occur together.

But each word also contains information that we want to capture. Like about the relationships between characters and within characters and so on. This is where character-based n-grams come in and this is what “subword” information that the fasttext paper refers to.

So the way fasttext works is just with a new scoring function compared to the skipgram model. The new scoring function is described as follows:

For skipgram you could see, we took a dot product of the two word embedding vectors and that was the score. In this case, it takes a dot product of not just the words but all it’s corresponding character n-grams from 3 to 6. So the word vector for the word will be the collection of the n-grams along with the word.

“hello” = {hel, ell,llo,hell,ello, hello}

“assumption” = {ass, ssu, sum, ump, mpt,pti, tio, ion,….., mption, assumption}

Each word “hello” and “assumption”’s vector representation would be the sum of all the ngrams including the word.

And that is the score function.

Now that we have the score function, let’s actually go ahead and implement the code for the same.

The libraries we will use are as follows:

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(13)

from keras.models import Sequential

from keras.layers import Embedding, Merge, Reshape, Activation, Flatten, Input, merge, Dense

from keras.layers.core import Lambda

from keras.utils import np_utils

from keras.utils.data_utils import get_file

from keras.utils.visualize_util import model_to_dot, plot

from keras.preprocessing.text import Tokenizer, base_filter

from keras.preprocessing.sequence import skipgrams, pad_sequences

from keras import backend as K

from keras.models import Model

from gensim.models.doc2vec import Word2Vec

from IPython.display import SVG, display

import pandas as pd

Using TensorFlow backend.

The Airbnb reviews dataset can be downloaded from the Airbnb data website here. The final results should be similar even if you do not use the specific review dataset.

corpus = [sentence for sentence in data2['text'] if sentence.count(" ") >= 2]

tokenizer = Tokenizer(filters=base_filter()+"'")

tokenizer.fit_on_texts(corpus)

V = len(tokenizer.word_index) + 1

vocab = tokenizer.word_index.keys()

This is the first important part. We need the corresponding character n-grams for each of the word The char_ngram_generator generates the n-grams for the word. The variables n1 and n2 refer to how many characters of n-grams should we use. The paper refers to adding a special character for the beginning and the end of the word so we have n-grams from length 4 to 7. Also for each of the words, the list also contains the actual word other than the corresponding n-grams.

#This creates the character n-grams like it is described in fasttext

def char_ngram_generator(text, n1=4, n2=7):

z = []

# There is a sentence in the paper where they mention they add a

# special character for the beginning and end of the word to

# distinguish prefixes and suffixes. This is what I understood.

# Feel free to send a pull request if this means something else

text2 = '*'+text+'*'

for k in range(n1,n2):

z.append([text2[i:i+k] for i in range(len(text2)-k+1)])

z = [ngram for ngrams in z for ngram in ngrams]

z.append(text)

return z

ngrams2Idx = {}

ngrams_list = []

vocab_ngrams = {}

for i in vocab:

ngrams_list.append(char_ngram_generator(i))

vocab_ngrams[i] = char_ngram_generator(i)

ngrams_vocab = [ngram for ngrams in ngrams_list for ngram in ngrams]

ngrams2Idx = dict((c, i + 6568) for i, c in enumerate(ngrams_vocab))

ngrams2Idx.update(tokenizer.word_index)

words_and_ngrams_vocab = len(ngrams2Idx)

print words_and_ngrams_vocab

50993

char_ngram_generator("hello")

['*hel',

'hell',

'ello',

'llo*',

'*hell',

'hello',

'ello*',

'*hello',

'hello*',

'hello']

new_dict = {}

for k,v in vocab_ngrams.items():

new_dict[ngrams2Idx[k]] = [ngrams2Idx[j] for j in v]

Even though we are not using our own layer in Keras, Keras provides an extremely easy way to extend and write one’s own layers. Here is an example of how one can add all the rows of a matrix where each of the rows represents each char-ngram to get the overall vector for the entire word. This is the key idea behind the subword information of each word. Each word is essentially the sum of all it’s corresponding vectors of it’s n-grams.

from keras.engine.topology import Layer

class AddRows(Layer):

def get_output_shape_for(self, input_shape):

shape = list(input_shape)

assert len(shape) == 3 # only valid for 3D tensors

return tuple([shape[0],shape[2]])

def call(self, x, mask=None):

return K.sum(x, axis=1)

Here is the network. Each word can have the only certain number of n-grams. Here we are limiting that to 10. Each of these n-grams along with the word is then trained and we get a corresponding vector for each of the word and the ngrams in the word. The n-grams are a superset of the vocabulary. Also because we first created a dictionary of words and then a dictionary of the char n-grams, the word “as” and the bigram “as” in the word “paste” are assigned to different vectors. Finally, we add the corresponding vectors of n-grams in each word to get the final representation of the word from the corresponding char n-grams and do a dot product of these two vectors to find the similarity of these two words. Notice that the difference with normal skip-gram in word2vec is just that this time each word also has the information of the corresponding character n-grams. This is the subword information it refers to.

maxlen = 10

dim_embeddings = 128

inputs = Input(shape=(maxlen,), name = 'inputWord',dtype='int32')

context = Input(shape=(maxlen,), name = 'contextWord',dtype='int32')

embedded_sequences_input = Embedding(200000,

dim_embeddings,

input_length=maxlen,

name='input_embeddings',

trainable=True)(inputs)

embedded_sequences_context = Embedding(200000,

dim_embeddings,

input_length=maxlen,

trainable=True,

name='context_embeddings')(context)

embedded_sequences_context1 = Lambda(lambda s: K.sum(s, axis=1), output_shape=lambda s: (s[0],s[2]))(embedded_sequences_context)

embedded_sequences_input1 = Lambda(lambda s: K.sum(s, axis=1), output_shape=lambda s: (s[0],s[2]))(embedded_sequences_input)

# embedded_sequences_input1 = Reshape((1,), input_shape=(1,128))(embedded_sequences_input1)

# embedded_sequences_context1 = Reshape((1,), input_shape=(1,128))(embedded_sequences_context1)

final = merge([embedded_sequences_input1, embedded_sequences_context1], mode='dot', dot_axes=1)

# final = Reshape((1,), input_shape=(1,1))(final)

final = Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')(final)

model = Model([inputs, context], final)

model.compile(loss="binary_crossentropy", optimizer="rmsprop")

display(SVG(model_to_dot(model, show_shapes=True).create(prog='dot', format='svg')))

words_and_ngrams_vocab

Finally, we train the network with the various aspects we discussed.

corpus = [sentence for sentence in data1['text'] if sentence.count(" ") >= 2]

tokenizer = Tokenizer(filters=base_filter()+"'")

tokenizer.fit_on_texts(corpus)

V = len(tokenizer.word_index) + 1

maxlen = 10

for _ in range(1):

loss = 0.

for doc in tokenizer.texts_to_sequences(data1['text']):

# print doc

data, labels = skipgrams(sequence=doc, vocabulary_size=V, window_size=5, negative_samples=5.)

ngram_representation = []

ngram_contexts = []

ngram_targets = []

for j in data:

ngram_context_pairs = []

word1 = new_dict[j[0]]

word2 = new_dict[j[1]]

ngram_contexts.append(word1)

ngram_targets.append(word2)

ngram_context_pairs.append(word1)

ngram_context_pairs.append(word2)

ngram_representation.append(ngram_context_pairs)

ngram_contexts = pad_sequences(ngram_contexts, maxlen=10, dtype='int32')

ngram_targets = pad_sequences(ngram_targets,maxlen=10,dtype='int32')

X = [ngram_contexts,ngram_targets]

# print len(ngram_contexts[0])

Y = np.array(labels, dtype=np.int32)

# print ngram_contexts.shape, ngram_targets.shape, Y.shape

if ngram_contexts.shape[0]!=0:

# loss += model.train_on_batch(X,Y)

try:

# print "tried"

loss += model.train_on_batch(X,Y)

except IndexError:

continue

print loss

We save the weights just so we can use it with gensim, for simple experimentation.

f = open('vectorsFastText.txt' ,'w')

f.write(" ".join([str(V-1),str(dim_embedddings)]))

f.write("\n")

vectors = model.get_weights()[0]

for word, i in tokenizer.word_index.items():

f.write(word)

f.write(" ")

f.write(" ".join(map(str, list(vectors[i,:]))))

f.write("\n")

f.close()

Now that we have the words, let’s see how the word vectors did! This is the Airbnb reviews dataset, so let’s do some exploration on the word vectors we just created.

from gensim.models.doc2vec import Word2Vec

import sys

import codecs

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

w2v = Word2Vec.load_word2vec_format('./vectorsFastText2.txt', binary=False)

w2v.most_similar(positive=['nice'])

[(u'very', 0.4748566746711731),

(u'kind', 0.45726102590560913),

(u'easy', 0.433699369430542),

(u'person', 0.42663151025772095),

(u'responsible', 0.41765880584716797),

(u'friend', 0.41492557525634766),

(u'likes', 0.4143773913383484),

(u'accommodating', 0.40841665863990784),

(u'polite', 0.4058171212673187),

(u'earth', 0.4037408232688904)]

w2v.most_similar(positive=['house'])

[(u'apartment', 0.562881588935852),

(u'private', 0.525530219078064),

(u'hope', 0.49403220415115356),

(u'beautiful', 0.48529505729675293),

(u'studio', 0.46020960807800293),

(u'room', 0.46016234159469604),

(u'this', 0.4449312090873718),

(u'location', 0.4436565637588501),

(u'were', 0.44244450330734253),

(u'our', 0.43545401096343994)]

w2v.most_similar(positive=['clean'])

[(u'organized', 0.6887848377227783),

(u'neat', 0.6856114864349365),

(u'responsible', 0.6010746955871582),

(u'polite', 0.5982929468154907),

(u'tidy', 0.5712572336196899),

(u'keep', 0.5637409687042236),

(u'respectful', 0.5535181760787964),

(u'courteous', 0.5482512712478638),

(u'warm', 0.5135964155197144),

(u'easy', 0.5043907165527344)]